Capstone’s European Technology 2023 Preview: EU’s Focus on Bolstering Its Autonomy and Competitiveness Boosts Risks for Big Tech, Opportunities for Chip Makers

December 20, 2022

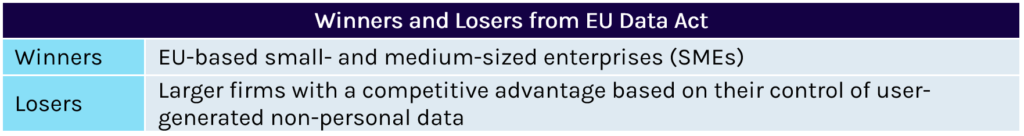

Capstone believes that European policymakers will increasingly prioritize the EU’s strategic autonomy and global competitiveness in the TMT sector. Policymakers are concerned about the strategic dominance and unparalleled ability of Big Tech firms to leverage data across their ecosystems. Lawmakers also want to bolster the EU’s semiconductor manufacturing capacity and reduce its exposure to supply chain and geopolitical risk.

We believe an increasing focus on competitiveness could give rise to several underappreciated risks and opportunities for global technology firms operating in Europe. The EU Data Act and Chips Act will be signature legislative packages to pass in 2023. The EU legal framework to protect competition is evolving and has been supplemented by new regulation – EU Digital Markets Act (DMA). Big Tech platforms will be designated as gatekeepers under the Act in 2023, and formal enforcement will commence in 2024.

EU Data Act

EU Data Act to Level the Playing Field for Data Economy, Prioritize Competition and Data Sovereignty; Ramps Up Scrutiny for Cloud Providers

The EU’s Data Act, proposed by the European Commission on 23 February 2022, constitutes a key pillar of the European strategy for data. The goal is to create a single market for non-personal data to ensure the EU’s global competitiveness and data sovereignty.

The Act will define how the European data economy will distribute value among economic operators, foster competition, provide user choice, and create opportunities for innovation. Put more simply, the Data Act is intended to level the playing field by defining who can create value from data and under what conditions.

IoT Data: A key focus will be on data generated by users of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, such as smart home applications (for example, Amazon’s Alexa), and ensuring easier access to unlock its value. The draft act imposes an obligation on data holders to make it available to users and third parties at the request of users for free and without undue delay. The draft also clearly states that manufacturers of smart IoT devices do not have exclusive rights over the databases which contain data generated by the use of a product or service.

While manufacturers will likely continue to exploit data from products and rely on trade secrets protection, they will no longer be able to assert a competitive advantage solely through exclusive control of data collected by products they manufacture.

Big Tech Excluded: Notably, the European Commission proposal excludes tech companies designated as gatekeepers under the Digital Markets Act from benefiting from the data-sharing provisions. Some Members of the European Parliament have suggested extending the ban to all companies that have a dominant position in the data market.

Contractual imbalances: Another provision aimed at leveling the playing field takes aim at the terms in data sharing contracts between businesses. The European Commission plans to prepare model contracts for these situations to ensure the terms are fair. SMEs are set to gain negotiating power.

Cloud: Data processing services, such as cloud and edge computing providers also face potential headaches from provisions that would make it easier for users to switch between services, while being given the entitlement to functional equivalence post-switching. While there is an exception for technical unfeasibility, the burden of proof is on the service provider. Furthermore, the Act would mandate cloud services providers to prevent the transfer of non-personal data held in the EU where such a transfer or access would create a conflict with EU law.

The Data Act is intended to level the playing field by defining who can create value from data and under what conditions.

An overly protectionist final text may deepen tensions around transatlantic data flows by clearly favoring providers based in the EU over large US cloud players currently dominant in Europe.

The Data Act is currently in the trialogue stage, being debated in the EU Parliament and Council. The final text is expected to be established in 2023, and it will likely enter into force around mid-2024

EU Chips Act

EU Chips Act to Provide Over €10B in Subsidies for Intel, STMicroelectronics; Excess Profit-Sharing Mandate and Geopolitical Risk Could Sour Benefits

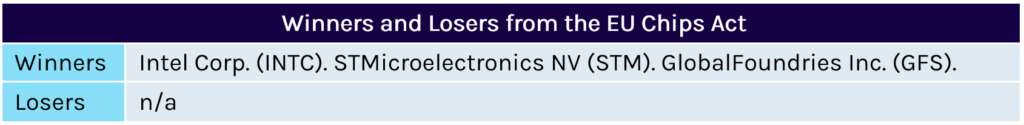

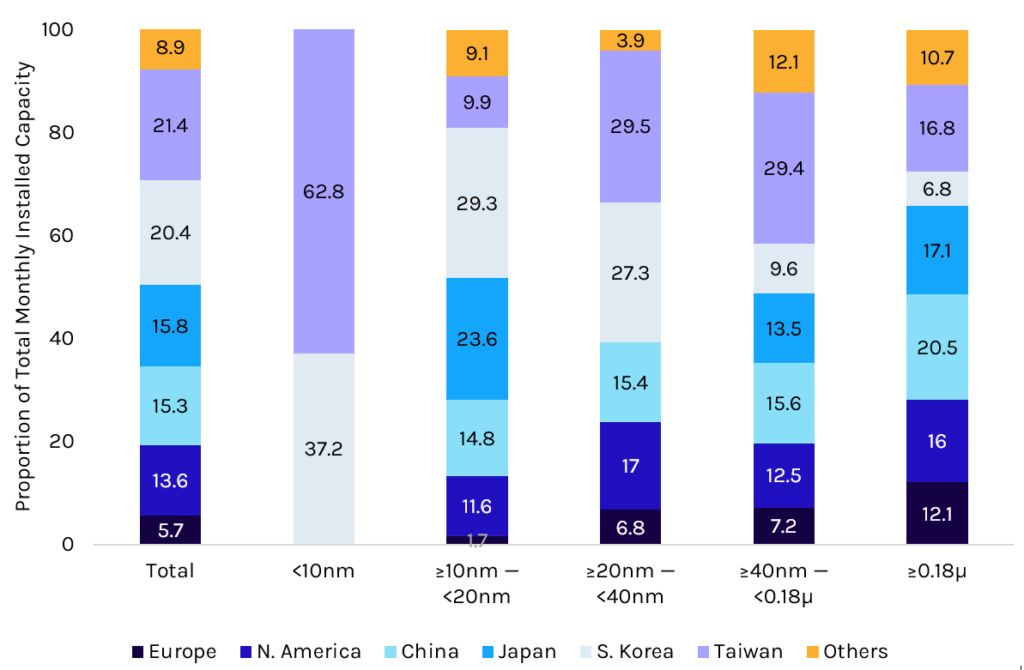

In December, the 27 governments of the EU Council agreed on a joint position on the EU Chips Act, which we believe will be implemented in Q2 2023, allowing Member States to provide subsidies to chip manufacturers and speeding up the issuing of permits. The EU wants to enhance its semiconductor supply chain security and bolster its economic and technological competitiveness vis-à-vis the US and China, with the aim of having 20% of the global share in semiconductor manufacturing by 2030.

Exhibit 1: Integrated Circuit Capacity by Region

Capstone believes Intel Corp. (INTC) will receive subsidies in excess of €8B from the German and Italian governments between Q2 2023 and Q4 2024. The French government will provide funding to a joint plan by STMicroelectronics NV (STM) and Globalfoundries (GFS) to build a €5.7 billion semiconductor manufacturing facility. Government support has yet to be disclosed but, based on the recent precedent of roughly 25% to 40% of funding coming from governments, we expect it to amount to between €1.4 and €2.3 billion. The decisions are pending state aid approval from the European Commission.

The Chips story in Europe will continue to play out in 2023.

This raft of subsidies, if granted, will also likely benefit other firms in the broader supply chain, such as ASML Holdings NV (ASML on the Amsterdam exchange).

STMicroelectronics has received state aid approval for it to receive €292.5mn of subsidies from the Italian government to help it fund a €730 million factory in Italy. It would be the first industrial scale, integrated epitaxy silicon carbide (SiC) wafer production line in Europe. We highlight, however, that as a condition of receiving the funding, it is required to satisfy EU priority-rated orders first in a supply shortage and also has to “share potential additional profits beyond current expectations with Italy”. The threshold for additional profits has not been disclosed, but such conditions, if imposed, could sour the overall benefit of the package. More generally, such mandates could potentially set a troubling precedent for other state aid decisions. Capstone expects the first state aid approval for Intel in 2023.

The Chips story in Europe will continue to play out in 2023, for 3 key reasons:

- Outstanding subsidies: European Governments still have earmarked subsidies outstanding. For instance, the Spanish government still has €12.25 billion of subsidies available to distribute to companies in the sector, as it has yet to come to terms with any firms yet. Notable subsidy candidates include Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TMSC) and Samsung Electronics, whose CEO Lee Jae-yong met with Spanish PM Pedro Sanchez in November.

- Political negotiations: The legislative process of the Act has not been finalized and the European Parliament is yet to have its say. As we highlighted, smaller Member States are concerned with how the direct benefits of the Act flow to larger Member States, Germany, Italy, and France. While we think the aforementioned Member State subsidies are safe from the politics, there is likely to be more heated discussions regarding a separate fund proposed by the Commission. The proposal would use €3.3 billion of EU cash and involve the participation of the European Investment Bank (EIB) to fund semiconductor firms (expected to be SMEs) to undertake research and development through grants, loans and equity-financing.

- Geopolitics: National security issues will continue to present risks. For instance, Liesje Schreinemacher, Trade Minister for the Netherlands which is home to ASML, confirmed in October that she is in discussions with the US to implement new export controls. While the Dutch government has not granted the firm licences to export its most advanced machines to China, as they could be used for military applications, it still had sales to customers in China of over €2 billion in 2021, which could be threatened by an expanded scope of export controls.

Data Privacy

EU Competition Authorities Empowered to Consider Data Privacy

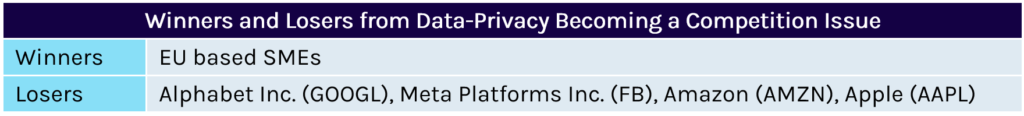

Athanasios Rantos, the Advocate General (AG) at the Court of Justice for the EU (CJEU) in September handed down a significant opinion on a high-profile case which will likely empower European competition authorities to consider data protection breaches in their investigations. While the AG’s opinion is non-binding, the court follow’s the AG opinion in 85% of cases. A final decision expected in the coming months.

AG Rantos opined that while competition authorities do not have direct jurisdiction to enforce non-antitrust legal frameworks, including the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), they may review a company’s privacy practices and take these into account to determine if a company is abusing its dominant position.

The case was referred by the German federal competition authority, which prohibited Meta Platforms Inc. (META)-owned platform Facebook from processing personal data according to its terms of services as it failed to comply with the General Data Protection Regulation. One of the key questions referred to the CJEU was whether a GDPR violation could constitute an abuse of dominant position.

The ruling, if it follows Rantos’ direction, will pave the way for EU competition authorities to scrutinize personal data practices of large tech firms, likely to support an ongoing trend of applying novel theories of harm in EU competition cases. If competition infringements are found, fines are likely to be higher than for GDPR infringements. The maximum fines, although rarely handed down, is 10% of total annual worldwide turnover as opposed to 4% under GDPR.

More clarity on provisions, including what this additional consent will look like is expected throughout 2023, however, a formal position on what big tech will need to change is expected in 2024.

The enhanced scrutiny of company’s data practices in 2023 will come in addition to the EU Digital Markets Act (DMA) and Digital Services Act (DSA) – a new regulatory framework for big tech seeking to remold aspects of established digital markets.

The DMA also treats certain personal data practices as a competition concern, for example it specifically prohibits the combination and cross-using of personal data for targeted advertising purposes without explicit and clear user consent. More clarity on provisions, including what this additional consent will look like is expected throughout 2023, however, a formal position on what big tech will need to change is expected in 2024. The ongoing work and findings of the newly empowered national competition authorities will also feed into DMA enforcement.