Continued State Involvement in Tech, a Boon for Chips and Computing, Remains Underappreciated

By Gabe Armstrong-Scott, JB Ferguson, and Ian Tang

January 11, 2023

Capstone believes heavy-handed state regulation of China’s tech industry is here to stay, despite broader market expectations that the government’s crackdown is near its end. In 2023, China will set and enforce policies that require technological development and innovation to occur hand-in-hand with the state.

Private companies will have to abide by a higher “new normal” level of state integration in corporate governance and avoid conduct that runs afoul of the regulators or the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). They will also be encouraged to innovate, so long as they stay in line with CCP objectives. For some companies this will prove burdensome, while for others it will bolster their success. China will likely limit its highly public IPO-scrapping politics of the past three years due to economic pressures. Instead, the CCP will more quietly move to integrate itself with the private tech sector.

Platform companies will broadly be negatively impacted by greater state involvement. However, some tech giants like Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. (9988 on the Hong Kong exchange) and Tencent Holdings Ltd. (0700 on the Hong Kong exchange) are beginning to adapt to the heavy state supervision and integration. That entails cooperating with the state by focusing on products less likely to be subject to domestic political issues (such as computing), and, in some instances, integrating its corporate and operational governance and shedding platform economy investments.

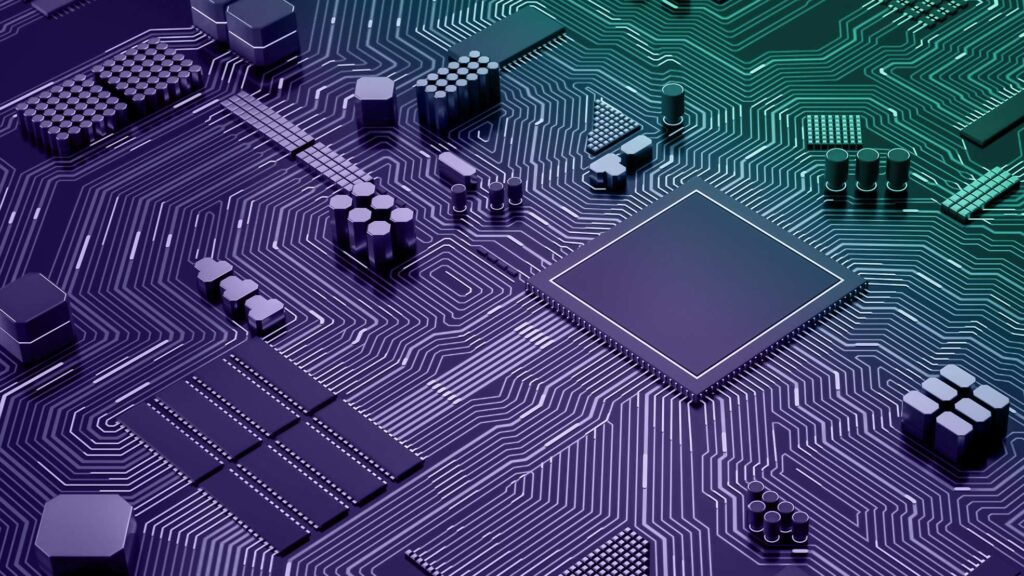

Industrial tech products are the major winners, with China staking much of its future growth on developing products like high-end semiconductors and photonic silicon chips, cloud/quantum/satellite-integrated terrestrial computing, and driverless and electric vehicles (EVs). These products will benefit from state investment and industrial policy in 2023. Economic and social pressures are also pushing the CCP to liberalize its Zero Covid regime, bolstering tech manufacturing.

What China Wants: Technological Innovation With Chinese Characteristics

While many observers claim China’s crackdown on technology companies is nearly over, Capstone believes that this is far from true. Following two decades of explosive growth and little regulation of the Chinese “platform economy,” an era of heavy state influence and strict regulation in its domestic tech industry has begun. Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, who has made centralizing power and bolstering CCP control of Chinese society the cornerstone of his rule, this trend has little hope of abatement, no matter the economic pressures.

Just as the West looked on with surprise when China’s economic liberalization in the 1980s-90s failed to result in democratization, Capstone believes that the CCP will also try to conduct technological development in its own characteristic way, with the Party’s political ideology — “socialism with Chinese characteristics” – at its core. China does not see state regulation as anathema to technological innovation, as is common in the West. Tech companies will be forced to operate within a staunchly Marxist-Leninist socialist market economy, with CCP integration a necessity for any powerful company or product. While the CCP may not be a master at picking winners or fostering innovation, it can make losers of tech giants at a moment’s notice

China will set policies that force technological development and innovation to occur hand-in-hand with the state and companies will — as a matter of survival — have to abide by stricter state regulations and incorporate CCP ideology in their products.

How we got here: Jack Ma’s hubris and the rise of Big Tech in China

In 2021 and 2022, the CCP finally began to flex its regulatory muscle following the meteoric rise of Chinese Big Tech companies in global markets. Three or four Chinese tech firms have consistently ranked in the top 10 global technology companies by market cap starting around 2018, and using the output of the private tech industry has become a near-necessity for day-to-day living in China.

The Chinese tech boom led to the emergence of a powerful tech entrepreneurial class and the permeation of private industry influence and control across nearly all aspects of Chinese society and economy. That influence was manifest in areas that included information flows and communications, detailed data collection at gargantuan scales, and economic necessities including digital payments and travel passes.

Some among the class of powerful tech entrepreneurs eventually overstepped the CCP line, breaching acceptable degrees of outspokenness or power and influence over Chinese society (such as Jack Ma’s criticisms of the CCP in 2020). This, coupled with Xi’s fear that a privately-owned tech infrastructure that underpinned much of China’s society posed a risk of undercutting CCP objectives and state institutions, prompted a crackdown.

The October 2020 suspension of Ant Group’s planned initial public offering (IPO) in New York and Hong Kong showed how the CCP could, with a wave of its hand, halt a deal that was expected to raise $34.5 billion (it would have been at the time the world’s largest-ever IPO). Similarly, in 2021, the CCP showed tech platforms that it ruled the roost when it suspended ridesharing giant Didi Chuxing (owned by Tencent) from Chinese app stores. Chinese regulators also eliminated the for-profit ed-tech industry in China, imposed onerous licensing requirements for video games – virtually banning violent content – and limited gaming for people younger than 18 to three hours per week. Chinese companies have rushed to file for local IPOs in Hong Kong and Shanghai.

Today, amid sluggish economic growth and some social and health dilemmas stemming from its Zero-Covid Policy, China faces ample internal pressure to open up its economy and stimulate private enterprise in 2023. Chinese regulators have also concluded some investigations into technology platforms, including Jack Ma’s Ant Group and Tencent’s Didi Chuxing, which is a win for Didi Chuxing’s shares and the prospects for Ant Group’s eventual IPO. However, official Chinese statements, policy planning documents, and draft legislation suggest that these developments should not be taken to mean the CCP will take a hands-off approach when it comes to state control and regulation of the domestic tech industry. China’s leaders remain in full control over the mechanisms through which its companies raise money from investors.

However, due to economic pressures, Capstone believes that China will likely limit its highly public IPO-scrapping politics of the past three years. China likely expects that the domestic signaling and power-play tactics it has employed over the past two years have hampered the ability or willingness of private enterprises to make major moves that could undermine the CCP in the near-term. Instead, the CCP will more quietly move to integrate itself with the private tech sector.

China’s Domestic Tech Policies: What to Expect

Chinese regulators are currently considering broad new regulatory regimes to address various tech platform transgressions and limitations, in addition to those introduced this year. (Those include onerous licensing requirements for video games, favoring non-violent, pro-CCP themes.) This will highly likely include new or updated regulations on:

- Mandated structural changes to corporate governance and ownership. We expect Chinese regulators to mandate or encourage changes in the structure of certain tech companies on an ad hoc basis, including mandating state ownership of shares and/or operations of certain companies. For instance, Alipay accepted partial state-ownership, and Tencent has divested from several partially owned platform companies, seemingly to escape the ire of China’s regulators. We are likely to see more of this in 2023. Amid US-China technology decoupling, this trend will harm Chinese corporations that want to attract foreign investment or operate internationally, given that links to the CCP increase the likelihood the US will brand them a risk to its national security. In particular, digital financial payments systems like WeChat Pay and Alipay are likely to experience structural changes, as Beijing is worried about their ability to undercut state-owned banks and the Renminbi.

- Mandated full or partial state control related to securitized industrial products (i.e. matters of national security) is inevitable. Chipmakers, EV and driverless vehicle manufacturers, quantum computing centers, biotech manufacturers, and digital payments systems all fall under this category. Subsidies for core industrial “winners” like photonic silicon chips and industrial policy more broadly under Made in China 2025 will supplement China’s drive to boost these products.

- Further regulations (and their implementation) relating to recommendation algorithm design and usage. For large Chinese technology firms, last year’s revelation that the CAC has been investigating the algorithms of Alibaba Group , Tencent, and privately held ByteDance (owner of TikTok) served as a cause for concern, among other regulatory themes. The 2022 Provisions on the Administration of Recommendation of Internet Information Service Algorithms are far-reaching and comprehensive, including a mandate that algorithm recommendation service providers “actively disseminate positive energy, and promote the application of algorithms upward and good,” to a prohibition of algorithms that “violate public order and good customs, such as inducing users to over-indulge or over-consume” or the use of algorithms to engage in anti-competitive behavior or activities that threaten national security.

- Protections for individuals: Gig-worker protections, privacy protections, international data transfer restrictions, and anti-trust regulations are all currently being strengthened and will be rolled out in the next one to two years.

- Other emerging tech in the private sector: Deepfake, generative AI, and “metaverse” companies in China will face regulatory scrutiny from the get-go as companies attempt to roll out these products more widely. Web3 is a non-starter for the Chinese government given its decentralized, user-controlled infrastructure – it will inevitably run into regulatory hurdles, though no timing has been indicated by regulators.

Implementation

Chinese technology law tends to be vague and sweeping, allowing the state government to prosecute cases as it wishes. The precise terms of the regulations are not what matters most. Instead, regulations serve as a deterrent against transgressions and as a broadly permissive tool for regulators to crack down on the most powerful players if deemed necessary.

Companies unable to adapt their business models with ease to abide by CCP requirements will struggle in this new environment and risk losing sizeable profits. For some companies, stricter standards mean limiting customer- and sales-focused innovation of their products, while greater state involvement in operational activities tends to create difficulties in day-to-day product functionality.

China’s Economic Priorities for 2023: Where Does Tech Fit In?

China held its annual Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC) in December 2022, during which the economic priorities of the year were laid out in broad terms (to be followed by a tangible work program in early 2023).

It is clear from official state documents that there is anxiety within the CCP about the economic and social pressures that China currently faces (amid the spread of covid-19 and the economy’s declining growth rate). There is immense pressure on the state to quickly find a remedy for the situation. Capstone believes China will try to use industrial technology policy as a core driver of economic growth in 2023 but will not significantly ease up on the platform economy, despite an emphasis on greater private sector innovation.

The CEWC identified industrial technology policy as a core economic priority for 2023 and in the longer-term. It stated that China aims “to accelerate the construction of a modern industrial system.” A key focus will be development of the “weak links in parts and components,” giving “full play to the organizational role of the government in key core technological breakthrough” while also “highlighting the dominant position of enterprises in scientific and technological innovation.”

The CEWC also stated the need to support platform technologies’ leadership in development, job creation, and global competition. While some observers have taken this to mean the end of Big Tech regulation has arrived, we believe this is unlikely, though it may mean a slowdown in the highly public IPO-scrapping politics of 2021-2022. There will likely be fewer publicized crackdowns on tech giants, with companies now better attuned to the ramifications of shunning local regulations or overstepping the party line, having learned from Alibaba co-founder Jack Ma’s example. This is a positive for several of the largest technology platforms who have come under substantial pressure over the past two years, including Ant Group, Alibaba, Tencent, Meituan, and others.

The CCP has a clear bent towards greater foreign investment and stimulating private enterprise and consumer spending in the coming year – all things that will benefit Big Tech. A return to more normal levels of economic activity is also expected as zero Covid restrictions are eased. However, these tech giants will have to manage a more prolonged and internal struggle to maintain pace with CCP regulations and greater state involvement in corporate decision-making.

Industrial Goods to Fare Well Under Domestic Industrial Policy

Capstone believes that industrial “bread and butter” technologies of the 21st century, including Chinese electronics, hardware, components, computing, and vehicle (EVs and driverless) manufacturers, will fare well from a domestic regulatory standpoint. China is heavily invested in the success of products that will drive its geopolitical ambitions. These companies will, however, continue to bear the burden of coercive economic and national security policies from the US The CCP’s policy direction for 2023 states that “industrial policy should be developed simultaneously with security”, suggesting a high level of state involvement.

Beijing has focused much of its tech crackdown on Big Tech, digital platforms, and entertainment companies that were becoming too powerful in their influencing power over Chinese citizens, working against CCP control rather than for it. On the contrary, China sees hardware manufacturing and computing as the oil of the 21st century – the industrial bread and butter of China’s future economic growth and geopolitical power. These industries have also historically stayed away from products that go against CCP preferences. On the contrary, e-games are seen as corrupting youth, social media as feeding citizens influential information and potentially fueling anti-government sentiment, and digital payments as undercutting core state functions.

Beijing will therefore try to ensure that entrepreneurship and innovation are fostered in this domain and will invest heavily in Chinese alternatives to foreign advanced computing and semiconductor products. Beijing plans to bolster investment in Shenzhen and Guangzhou “innovation corridors”, considered to be China’s Silicon Valley, to support its Made in China 2025 goals.

We are likely to see more digital platform companies move into this space, too. Superapps such as Tencent and Alibaba are beginning to move into products formerly considered to be industrial goods; for instance, working on producing photonic silicon chips, satellite-terrestrial integrated computing, or vehicles (electric and driverless).

The Confounders: What Could Change Predicted Outcomes for Chinese Tech

Zero Covid

Regardless of what covid-19 policy China assumes, it will have a tough year ahead economically and socially.

Capstone believes China will ease some but overall maintain significant covid-19 lockdown measures to limit the impact on the Chinese health system. Another mass vaccination effort is likely to ensue, even as vaccination hesitancy among the Chinese populace is high. It is possible that President Xi Jinping will also strike a deal with European partners to import mRNA vaccines to help boost immunity among the Chinese populace. The current scientific literature suggests that the top Chinese vaccines (CoronaVac and Sinopharm) have been roughly as effective as mRNA vaccines at protecting against severe covid-19, but not as effective at preventing infection.

Industrial manufacturers will continue to be hit hard if lockdowns persist. There may be fewer rewards to be reaped from favorable industrial policies toward manufacturers if factories and R&D facilities are closed, or if workers revolt amid poor working conditions (think Foxconn factories). Much of the platform economy that depends on day-to-day economic activity will also depend on the extent of lockdowns. If China relaxes restrictions, it may experience a health crisis that similarly heavily impacts the economy writ large.

US Economic Coercion

China’s domestic technology policy for 2023 may be a boon for some companies and industries, but these industries may lose business from foreign investors and consumers in 2023 if they are targeted by US tech decoupling policies. In fact, those industries most likely to be favored by China’s domestic policies usually manufacture highly strategic products that are most likely to be targeted by the US (hardware, semiconductors, etc.). Investors will have to balance the net gain of those industries from domestic subsidies and other favorable policies from Chinese regulators, with the negative impacts of US tech decoupling and coercive economic policies.

Learn What We Expect For US Tech Amid US-China Tension Here: