By Adam Cotterill, Capstone Energy Analyst

March 6, 2023—The passage of two US energy bills in recent years—the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) in 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022—have been described broadly as a new chapter in US industrial policy. In response, and as a result of Russia’s weaponization of its fossil energy sector, the EU is also embarking on an energy-driven industrial revolution of sorts. Consistent with every period of industrial acceleration since the late 19th century, the success of these energy-driven industrial strategies will depend in large part on the global steel sector.

While the long-term availability of key decarbonization-critical metals and minerals has been much ballyhooed, relatively little ink has been spilled on steel: one of the basic foundational materials with which most new energy technologies will be built. Each incremental megawatt of community solar capacity added to the global energy grid will require 35 to 45 tons of steel. Similarly, the steel content per installed megawatt of offshore wind capacity will be in the range of 120 to 180 tons. Beyond wind and solar, the buildout of a multitude of other decarbonization technologies—electric vehicles, long-duration batteries, electrolyzers, and carbon capture facilities—will also generate a new source of demand for steel.

Beyond wind and solar, the buildout of a multitude of other decarbonization technologies will also generate a new source of demand for steel.

In the coming decade, the intensification of two policy-related tailwinds will drive notable changes in the structure and carbon intensity of US and EU steelmaking. Firstly, the growing focus on domestic content sourcing and the increasing protectionism of domestic heavy industry will provide new support for Western steelmakers that have struggled to compete in recent years with imported alternatives. Secondly, the growing scrutiny of lifecycle and sum-of-the-parts emission counting for new energy technologies will provide additional incentives and mandates for steelmakers to decarbonize their operations. The implications of these tailwinds are relevant both for steelmakers and for the clean energy sector writ large. As this decade progresses, we expect that policy scrutiny over the origin and carbon intensity of steel inputs will only intensify.

In the US, the IRA’s revisions to Sections 45 and 48 of the US Tax Code incorporated new domestic content preferences and incentives for domestically sourced materials. For the handful of Section 45 tax credits, a 10% bonus credit is available to projects certifying that a minimum threshold of construction inputs—including steel—were homegrown. Those thresholds are set to intensify in the coming years. In the EU, the combination of an Emission Trade System (ETS) and the implementation of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) will serve to protect domestic heavy industry subject to relatively more stringent decarbonization requirements from being supplanted by cheaper, more carbon-intensive foreign alternatives while also incentivizing decarbonization. The US and EU may differ in their use of carrots versus sticks, but the outcome for steelmakers is consistent: a mandate to decarbonize, and incremental policy support to do so.

The US and EU may differ in their use of carrots versus sticks, but the outcome for steelmakers is consistent: a mandate to decarbonize, and incremental policy support to do so.

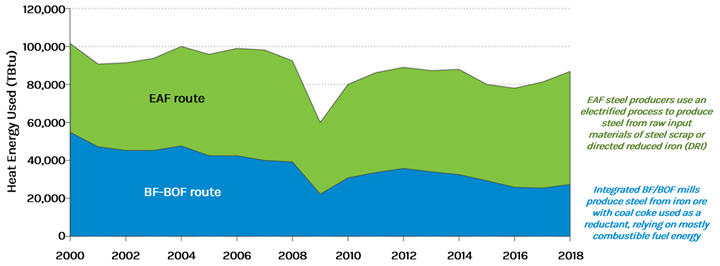

While the downstream outcome of deploying renewable energy and other decarbonization technologies may be net negative emissions, we expect the carbon intensity of upstream inputs like steel will become an increasingly relevant investment consideration. Today, the global steelmaking sector accounts for roughly 7% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. While steelmaking processes in the US and EU are undoubtedly less emission-intensive than foreign alternatives, thanks to the recycling of steel scrap and the investment in electric arc furnaces (EAFs), they are certainly not carbon-free. In 2018, roughly one-third of US crude steel was produced via the relatively more emissions-intensive blast furnace / basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) route (see Exhibit 1). The relatively slow decline in BF-BOF steelmaking processes, and the emissions produced by these mills, should not be shirked off.

Exhibit 1: Energy Consumption by US Steel Production Methods (2000-2018)

Source: US Department of Energy, Oak Ridge National Laboratory (2019)

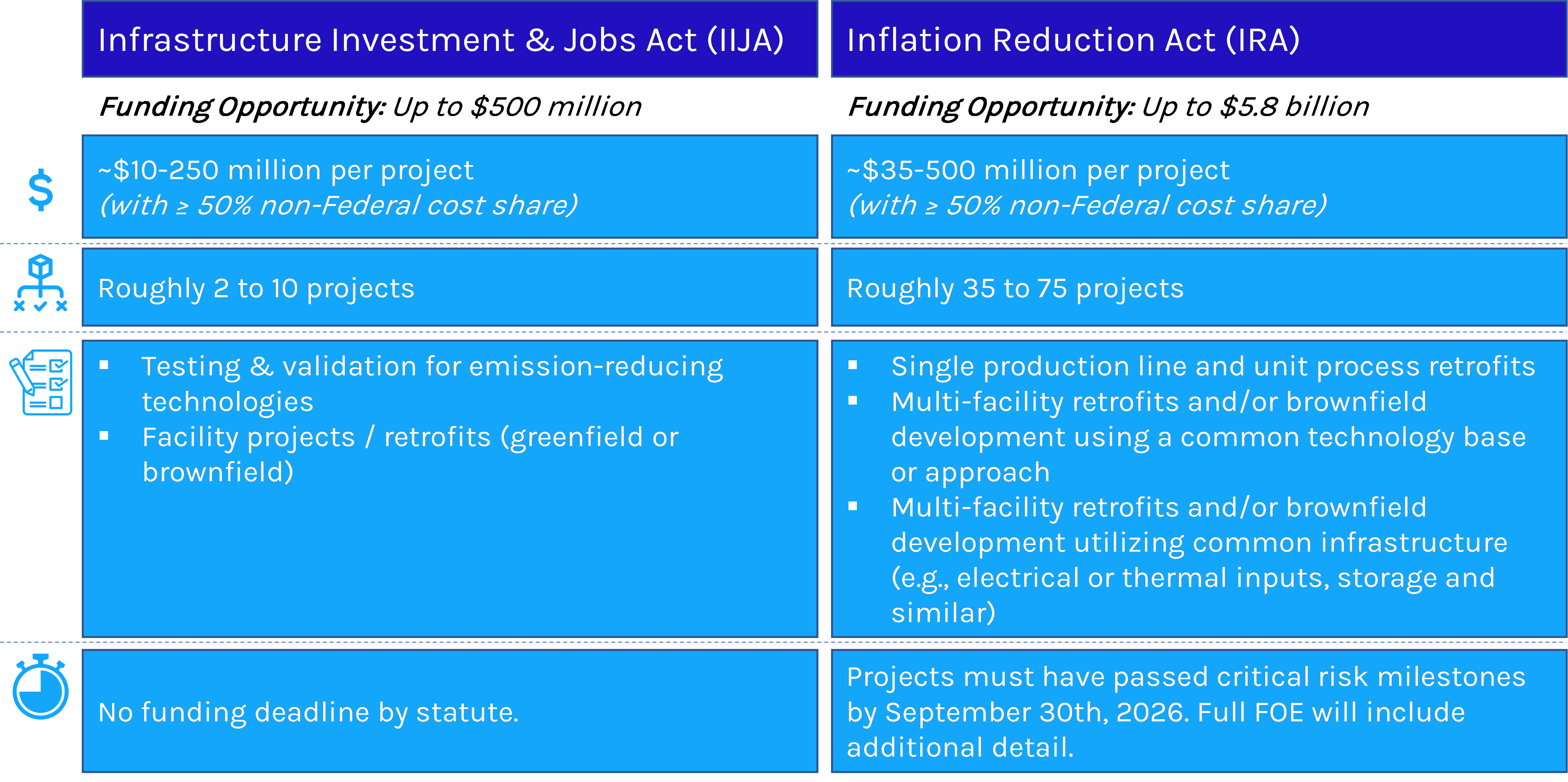

Through the IIJA and IRA, US policymakers included two tranches of funding opportunities for steel and other hard-to-decarbonize sectors, which we would encourage our clients to pay attention to. Most recently, in December 2022, the US Department of Energy (DOE) released a Notice of Intent in which it began to outline the process to apply for a piece of the $6.3 billion in federal funding made available to decarbonize the US industrial sector. Therein, it guided toward a release of the related Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) in March 2023. In a subsequent webinar held by the DOE’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) on January 24th, the agency provided the most prescription surrounding the program to date (see Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: DOE Industrial Funding Opportunities Anticipated Scope

Source: US Department of Energy

In addition to the DOE funding opportunities available directly to steel projects, the enhancements to the 45Q tax credit for carbon capture projects and the establishment of a new 45V tax credit for hydrogen production will also facilitate the long-term decarbonization of US steelmaking. Notably, there is no preclusion for projects receiving DOE funding to claim the aforementioned tax credits.

At a company level, the impending DOE funding opportunities will be incredibly impactful, supporting operators in making final investment decisions on new projects in the coming years by sharing in up to 50% of related project costs. The funding will also foster innovation in sectors that play an integral role in the construction and development of the global economy. However, in the context of the massive global steel sector, the policy commitments made by the US and the EU are simply a first step in the right direction. In the coming decade, the pace of decarbonization in the US and EU steel sectors—and the policymaking that underpins that decarbonization—will set the tone for the rest of the world. And then, in the 2030s, we will begin to see how broadly the to-be-determined steelmaking ‘best practices’ are adopted in the rest of the world.

In the coming decade, the pace of decarbonization in the US and EU steel sectors—and the policymaking that underpins that decarbonization—will set the tone for the rest of the world.

Based on the progress made by the global steelmaking sector towards reducing emissions over the last two decades—described by the International Energy Agency (IEA) as “Not on Track” to achieve decarbonization objectives—we expect that in a decade or two, we will look back at 2023 with a recognition that the consensus overestimated the speed at which the pursuit of low-emission steel was achieved. Particularly amidst projections of growth in global steel demand, we believe it is important not to underestimate the challenges we face in decarbonizing the litany of massive, global industrial processes of which steel is only one component. Similarly, it is important not to take for granted the companies that produce the commodities and material outputs on which our economy runs today. In the case of steel, a longer-than-expected timeline for decarbonization implies that the demand trajectory for metallurgical (met) coal will surprise public market investors to the upside over the coming decade. Therein, for capital market clients, an analysis of the handful of coal producers with outsized met coal exposure may be worth exploring.

Adam Cotterill, Energy analyst

Read more from Adam:

Rise of the Middle Powers: Why Fossil Fuel Supply Chains Will Upend the Global Status Quo

The Collision Course: Decarbonization Policy in an Energy Price Crisis

Read Adam’s bio here.