By Andrew Gier, CFA

August 3, 2021 — When it comes to climate policy, states, and California in particular, are often laboratories for policies that become more widespread and widely adopted. These policies are likely to build on lessons learned while developing existing programs and include models that have already proved successful in other areas. This often entails providing industry with financial incentives.

Politicians often somewhat ambiguously refer to the decarbonization of buildings as one of the next frontiers in climate policy. However, we believe the more tangible focus for policymakers in the coming years is one of the world’s most frequently used and oldest building materials: cement.

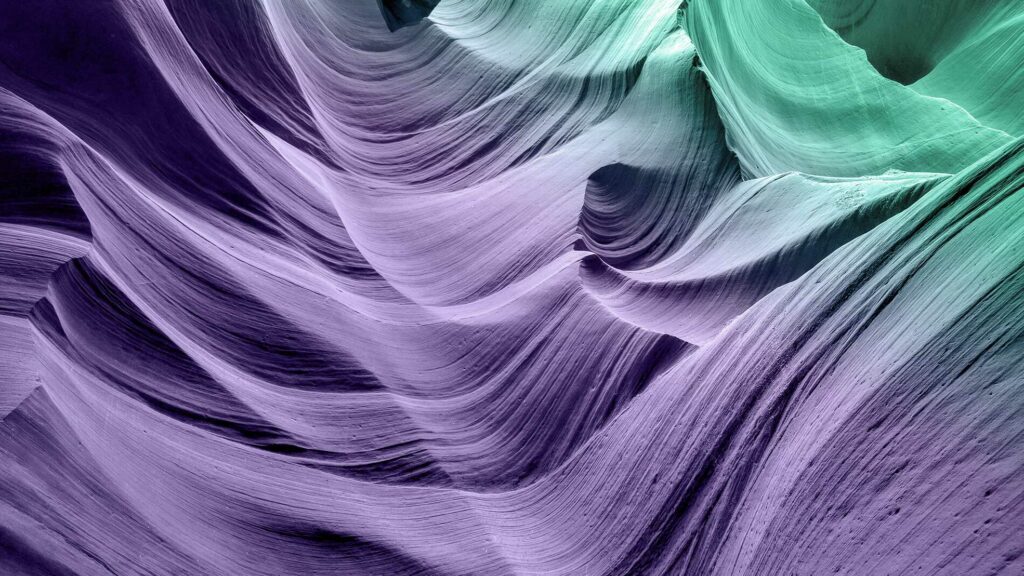

Variations of concrete and cement (a key ingredient that accounts for 80%–90% of emissions from concrete) have been used since humans first began to build cities. The World Cement Association reports that archaeologists found varieties of cement used as far back as 12,000 years ago. Although they are the product of millennia of evolution, concrete and cement account for nearly 10% of global CO2 emissions today and represent a larger share of emissions than every country in the world with the exception of the US and China.

Concrete’s significance in the effort to combat climate change is not lost on policymakers. In June, the California State Senate passed S.B. 596, a bill directing the California Air Resources Board (CARB) to develop a strategy to help the state’s cement sector reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 40% by 2035 and reach net-zero emissions by 2045. This would bring the state’s emissions-intensive cement sector in line with a 2018 executive order calling for economywide carbon neutrality by 2045.

S.B. 596 parallels another California program, which the Capstone Energy and Industrials team has done extensive work on—the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS). The bill specifically mentions the concept of life-cycle carbon intensity, which is at the heart of the LCFS program, and notes the importance of providing strong financial incentives and deadlines for decarbonization.

The LCFS is an attractive model for regulators for several reasons:

– It is fairly simple for market participants to understand and provides clear financial signals, driving tangible improvements in emissions;

– It is technology neutral, taking out some of the guess work associated with more proscriptive command-and-control regulations; and

– Perhaps most importantly, it extends the reach of California’s energy policy beyond the state’s borders. It gives out-of-state imports a higher carbon intensity and allows out-of-state producers to benefit from incentives for low-carbon production—driving interest in adopting similar policies in other states.

Though it got off to a slow start initially, the LCFS now provides a powerful policy incentive for low-carbon fuel producers. For renewable natural gas (RNG), a fuel with a particularly low-carbon intensity because of its ability to prevent emissions that would otherwise occur in the livestock sector, it is not uncommon for businesses to have more than 70% of their revenue tied directly to the sale of LCFS credits. The size of the potential revenue stream offered by the LCFS has spurred a 21st century California gold rush for developers in the biofuels sector.

If S.B. 596, or a similar bill is passed in California, we believe it will result in a program for concrete and cement that is in many ways similar to the LCFS. With time to meet California’s emissions reduction goals slowly running out, we believe financial incentives for low-carbon cement and low-emissions technologies in other sectors will manifest more quickly going forward. Whether the winners of an LCFS-like policy for the cement sector will be carbon capture and sequestration or some unrelated technology is anyone’s guess at this point. However, the writing is on the wall: Financial incentives are coming, and they will be substantial.

Cracks in Employer Insurance Create a New Market Opportunity

Capstone believes evolving dynamics in the employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) market will create opportunity for vendors operating in the self-funded, tax-advantaged account, and nontraditional insurance spaces. As rising premiums make fully insured ESI less viable,...