By: Josh Price and Cory Palmer

On day one of Joe Biden’s presidency, the United States re-entered the Paris Climate Agreement, committing to reach net-zero emissions economy-wide by 2050. While studies vary widely on the feasibility of this target, to achieve this goal, the US—and other countries—clearly need to significantly reduce the consumption of fossil fuels, raising concerns over the future of existing infrastructure assets. While at the World Economic Forum in January 2021, US Climate Envoy John Kerry argued “If we build out a huge infrastructure for gas now and continue to use it as the bridge fuel…we’re going to be stuck with stranded assets in 10 or 20 or 30 years.” Secretary Kerry’s observation is keen, but not necessarily absolute. Nevertheless, some midstream operators have begun positioning their companies for the transition, bifurcating their strategies to mitigate risks to their assets, while planning for alternatives in a low-carbon world — a strategy that is multi-faceted, multi-decade, and, they hope, flexible.

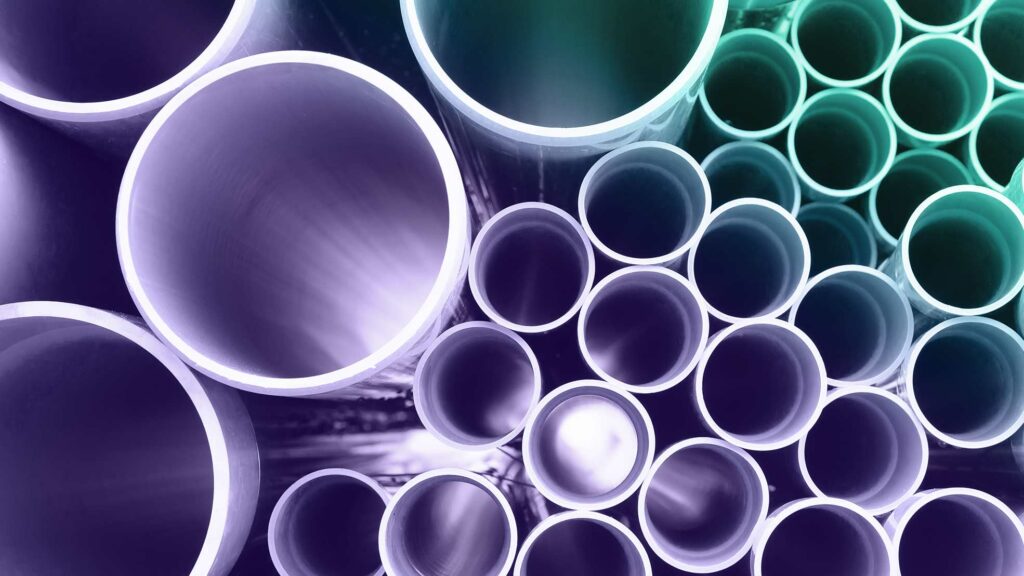

To mitigate this risk in the US, pipeline companies have begun a process at a key federal regulator, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), to shorten the economic life of their assets and update their depreciation schedules to recover costs more quickly through changing what customers pay to move oil and gas through the pipelines. Some companies argue the economic life of their assets will end in 2040 or 2050 due to climate regulation. We do not believe it’s so clear-cut. The value of existing pipelines will increasingly decouple from the demand for fossil fuels. Traditional asset and fuel operators abut the energy transition. Regulators (and customers) must begin to consider the most cost-effective way to decarbonize—including leveraging existing assets—or risk an energy shortage or higher energy costs. We believe existing oil and gas pipelines will see increased utilization by lower-carbon fuels and innovative uses of their rights-of-ways in the coming decades, mitigating the risk of the assets becoming stranded and the need to adjust rates.

We expect a policy-enabled reconfiguration of oil and gas pipelines, including for low-carbon technologies and innovative uses of property, will help mitigate the stranded asset risk.

Ongoing FERC considerations over the economic life of Berkshire Hathaway’s (BRK.A) Eastern Gas Transmission and Storage (EGTS) and Enbridge’s (ENB) Lakehead System serve as examples of how US pipeline operators are attempting to mitigate the risk posed by climate policies. On September 30, EGTS—which moves 9.5 bcf/d of natural gas—filed revised tariff language with FERC to increase effective rates for a variety of reasons. Of note, EGTS proposed a 29-year economic end life on its transmission assets versus the typical 35 to 40 years based on the Biden administration’s 2050 climate goals and other policies. Over 60 stakeholders filed motions to intervene, including EQT Corp. (EQT) which argued the truncated depreciation schedule is unjustified as it’s “based on predictions about future legislation and future costs” and “minimizes consideration of the availability of natural gas supply.”

Similarly, in May 2021 Enbridge asked FERC to adjust depreciation rates for its Lakehead system—which ships over 2.5 MMbbls/d of petroleum products—to reflect a truncation date of 2040 starting January 1, 2022. Enbridge argues climate policies will sharply reduce demand for crude and its Lakehead system is uniquely at risk given it provides 100% spot service which “will likely be the first barrels to be cut.” Enbridge’s existing facility surcharge projects have economic lives between 29-30 years. Canadian shippers on Enbridge’s system who would need to pay higher rates cheekily labeled the claim that the Lakehead system may be out of business in 18 years “remarkable given the entirety of the factual circumstances.”

While the complete shutdown of either EGTS or Lakehead in the next 20-30 years may seem farfetched—particularly considering the Energy Information Agency’s (EIA) 2050 energy forecast which FERC staff would likely leverage—these cases may create a dilemma for regulators in balancing consumer interest with climate goals. We do not expect stakeholders in either case to reach a resolution in the near term. Absent a settlement, this litigation will likely take several years, and any decision by an Administrative Law Judge would need to be approved by the commissioners which would likely set a precedent.

While both sides of the debate paint the situation as black and white concerning the extent climate policies will impact long-term fossil fuel demand, we believe there are several overlooked and underappreciated attributes of the assets and their contents that will mitigate the need to significantly reduce the economic life of assets. On the gas side, companies are testing the physical capability of systems to carry a blend of various types of hydrogen as utilities consider its use in power generation. The explosion of renewable natural gas (RNG) production in the US has also piqued the interest of utilities and regulators alike as designs are being approved that would allow for outsized compensation for the use of RNG in distribution networks.

In the liquids market, the boom of renewable diesel capacity and increasing interest in sustainable aviation fuels for the hard-to-abate heavy-duty and aviation sectors, respectively, will have longer-demand life given the lack of alternatives for those sectors for decades. Lastly, the path to operation for these assets should not be ignored. Permitting and rights-of-ways for these assets in itself can be a fungible commodity as it becomes increasingly difficult to construct long-line infrastructure in the US. Conversion of assets and property from gas or liquids carry to fill an increased demand for transmission in an electrified world could provide value and alternatives in the “last mile” of the transition.

While concerns over the future of existing oil and gas pipelines are understandable—particularly given the rhetoric from global leaders—we expect a policy-enabled reconfiguration of oil and gas pipelines, including for low-carbon technologies and innovative uses of property, will help mitigate the stranded asset risk. Pipelines companies are trying to mitigate this risk through depreciation rates, and time will tell whether regulators will recognize and integrate evolving climate objectives in to returns and set a new precedent or lean on the inherent uncertainty in future policy to balk at the prospects for change. Ultimately, we believe incumbent fossil fuel pipelines will continue to be a driver of value—not losses—even in a decarbonized world.