For administrations seeking sweeping regulatory change, the central obstacle is not political opposition, but the slow, procedural machinery of federal law. The biggest hurdle for a Trump administration that is looking to make sea changes in policy is not necessarily confirming appointees or issuing Executive Orders: it is the Administrative Procedure Act—a statute passed in the wake of the growth of New Deal agencies and the Second World War. We believe that investors, companies, and policymakers themselves often underappreciate the statute.

Why is the rulemaking process so important?

The Administrative Procedure Act (APA) is the core statute governing agency regulation in the United States and the rulemaking process for hundreds of federal agencies. These agencies may be bound by the statutes that give them power, but the APA is what allows them to craft the rules that implement those statutes.

The Trump Administration has consistently spoken about its plan to “unleash prosperity through deregulation,” but the federal government moves much more slowly than most things. The agency rulemaking process, which requires proposing and finalizing a regulation, a public comment process, and, in some instances, secondary review by the White House, generally takes several years to go from rule draft to proposed rule to finalized rule.

Following the finalization of a rule, the agencies will often face legal challenges. A large chunk of these cases are resolved at the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (DC Circuit), which takes, on average, about 12.7 months from the day a challenge is filed to when it is resolved (about 3 months longer than the average of all federal Circuit courts). If the court finds that a rule violated the APA, the traditional remedy is to vacate the rule and send the agency back to square one. What does this mean for an administration that wants to make a sea change to the federal government? It pays to be fast to be in office to defend rules, but to create long-term policy, the government must work within the strictures of the APA.

How is the Trump administration doing?

It is moving faster than the Biden administration, but the APA’s hurdles remain. One key way to gauge how a government is doing is to look at a small office within the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) called the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA). OIRA is one of the most quietly powerful organizations in the entire federal government, as it reviews and can change almost every important rule (or major guidance document) under Executive Order (EO) 12866. EO 12866 standardized much of the rulemaking process but, most importantly, mandated review of “significant” regulations. “Significant” regulations generally have an impact of more than $100 million per year on the economy, covering about 500-700 regulations (or certain major guidance documents) per year. OIRA’s review occurs at the end of the drafting process and can delay the planned release of a proposed or final regulation (particularly if the rule needs to go through review at both the proposed and final stages). OIRA traditionally has 90 days to review a rule, but the deadline can be extended. However, especially during the first year of an administration, rule reviews tend to be much faster.

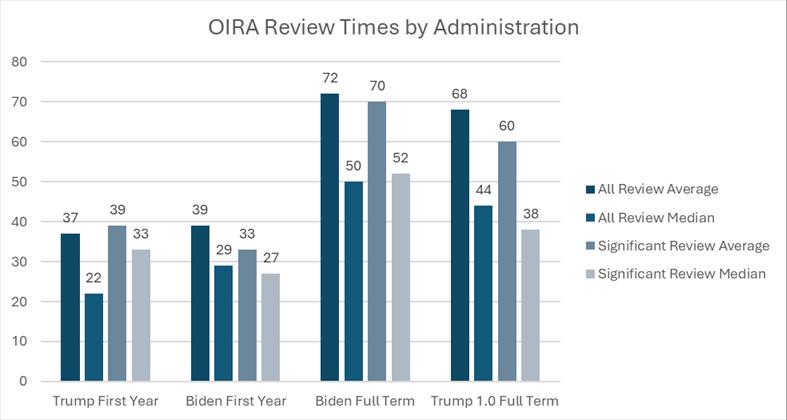

Exhibit 1: OIRA Review Times by Administration

Source: Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Capstone Analysis

Despite President Trump’s regulatory blitz, the timing of reviews has been remarkably similar to that of President Biden’s first year in office. The average and median review time for all reviews of regulations and guidance is slightly shorter than during Biden’s first year, but the review times for significant rules are slightly longer than during Biden’s first year.

Looking at some of the major rules the Trump administration has made into tentpoles of the first year of his administration, the timelines for some of these already appear to be slipping. The repeal of the 2009 Endangerment Finding, which set the basis for regulating greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles and other emission sources, has been a key issue for the administration, but the EPA has already missed its internal deadlines to finalize the rule by several months. The proposal was released at the end of July (on time, per administrative plans), but the final rule, planned for publication in September 2025, had not even reached OIRA for review by the end of 2025, arriving at the office for review on January 7, 2026.

The slowdown represents one of the major hurdles the Trump administration needs to jump over to truly change federal administrative policy: agencies are vast bureaucracies, and it takes a long time to turn such a large ship, especially if the penalty for making an error when turning the ship is that the ship goes back to its original bearing. Certain members of Trump’s administration, such as OMB Director Russell Vought, are keenly aware of OIRA’s role in keeping agencies in line, writing in a chapter of Project 2025 that “OIRA plays an enormous and vital role in reining in the regulatory state and ensuring that regulations achieve important benefits while imposing minimal burdens on Americans.”

What are we likely to see over the next three years?

The Trump administration will need to be more judicious about which regulations are high priority and which it thinks can be handled and defended during the latter part of the administration (or a potential future Republican administration in 2029). Getting important rules out and defended in court before the turnover of an administration is key, especially if the Trump administration wants its regulations to avoid the same fate that many late-Biden-era administrative actions have faced: the Trump administration choosing to defend the rule no longer or ask the court to send a rule back to the agency to rework or remove it.

In the end, policy revolutions in Washington are measured not by executive orders but by surviving rules. For the Trump administration, the next three years will test not the breadth of its agenda, but its ability to prioritize, execute, and defend rules before the clock runs out.

Read more from Walker:

The Environmental Services Industry’s Moment: PFAS, Water Utilities, and Other Coming Developments

Election Risks and Opportunities for Chemical Companies

The Battle Over Agency Authority: What’s at Stake in the November Elections