By: Gianna Kinsman

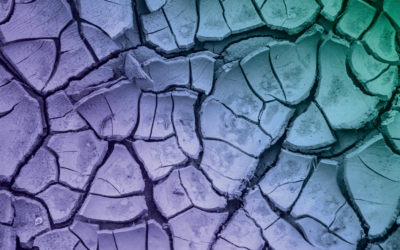

October 12, 2021 — As the Biden administration ramps up work to fulfill its campaign promise to control per- and polyfluoroalkyl (PFAS) chemicals, and it becomes clearer that manufacturers of the so-called “forever chemicals” face mounting risk of corporate liability and litigation, much of Capstone’s discussions with clients have centered around two conversations. The first being the potential imposition of significant new liabilities under the EPA’s Superfund authority, which allows the agency to go after polluters for the costs of cleaning up contaminated sites. The second conversation point typically centers on the potential development of new and costly drinking water standards for the best-studied, long-chain PFAS chemicals—and to what extent manufacturers may have to pick up the tab.

Capstone believes the regulatory and litigation risks facing Chemours Co., Dupont de Nemours, Corteva Inc., and 3M Co., from the use and disposal of PFAS, will continue to mount. We expect liabilities to reach $90 billion—developments we don’t believe the market fully appreciates. We’d like to highlight another layer of underappreciated risk that manufacturers and importers of PFAS products will have to reckon with—a risk that comes from a little-understood Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) statute.

The EPA’s Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention is now under the leadership of Dr. Michal Freedhoff, who formerly worked closely with Senator Tom Carper (D-DE) on PFAS issues on the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, and was key in crafting the 2016 reform to the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). The reform—often referred to as the Lautenberg act—gave the EPA more robust tools, resources, and enhanced scope to ensure the safety of chemicals.

Based on our conversations with experts and our own analysis, we believe that TSCA will be an important tool to help the Biden EPA achieve its PFAS regulatory goals.

Currently, EPA is getting more visibility into identifying potential sources of PFAS contamination and releases through two TSCA-based initiatives spurred by the Fiscal Year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). No less than 172 PFAS were added to the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) Program by Congress— a right-to-know program that informs communities about toxic chemicals to which they may be exposed—with further categories of reportable chemicals already added this year. We expect even more PFAS chemicals to be added to the TRI. An initial round of preliminary data was released this summer and is due to be finalized over the coming months, which is significant because the TRI’s mandate includes company reporting of releases and disposal methods.

Moreover, EPA now has a January 2023 deadline requiring a final reporting rule for over a thousand PFAS, from all manufacturers and importers of PFAS since January 1, 2011, for which EPA has already issued a proposal. Required reporting data includes chemical volumes, exposure data, disposal, and information the manufacturer has or could reasonably be expected to have on health and environmental impacts. The final rule will likely require the submission of data by the second half of 2023. Because of the lack of exemptions (even for producing PFAS byproducts while manufacturing something else, or importing finished products coated with PFAS) the proposal will likely capture entities that don’t have much historical experience in chemical reporting to EPA. With the involvement of small business advocates during the comment period, it’s possible the rule will include increased flexibility for these entities compared to the proposal, but exemption altogether appears unlikely.

Chemical approval processes, especially for PFAS, through the TSCA program have borne increased scrutiny since widespread reports this summer of issues of lax TSCA oversight for PFAS allegedly used in fracking. Under TSCA, EPA may prioritize chemicals for review. If EPA makes a finding of unreasonable risk, the agency then goes through a risk management rulemaking process and determines the appropriate action to eliminate the unreasonable risk. TSCA also allows for citizen petitions, under which anyone may petition EPA to regulate, restrict, or prohibit any existing chemical. As environmental and public health advocacy groups’ approaches grow more sophisticated, a petition accompanied by strong scientific data—especially submitted to an administration already signaling a muscular TSCA approach— may present a more expedient way to remove chemicals from the market that has so far been little-utilized.

EPA is also contemplating grouping PFAS by similar structural and chemical properties. The idea here is to organize PFAS into subgroups, where EPA can then prioritize one analog from each subgroup for initial testing. EPA’s signaled expansive use of testing powers was punctuated by an announced reconsideration of a petition for testing orders for Chemours (CC) on 54 PFAS, which likely will be decided by January 2022.

EPA also has a new general policy of disallowing new low-volume exemptions (LVEs) for PFAS, and is encouraging manufacturers to voluntarily withdraw approved PFAS LVEs and submit full premanufacture notification applications instead. This will drive new and potentially existing PFAS applications toward the PMN approval process, for which consent orders with strings attached is the most likely approval outcome. We believe these consent orders will include more stringent testing requirements, likely increasing compliance costs for manufacturers—stretching out or stalling new PFAS approvals.

The Biden EPA will also regulate finished products containing TSCA-regulated chemicals, presenting challenges to appropriately scrutinizing supply chains. In the case of PFAS, EPA has already removed a loophole for PFAS-coated products by withdrawing Trump-era guidance on the Significant New Use Rule for long-chain PFAS (e.g., PFOA, PFOS), meaning that imported products with PFAS as a surface coating (e.g., stain-resistant rugs) are subject to EPA review.

So, why should investors care? PFAS is used in everything from water-resistant clothing, stain-resistant furniture, and many other consumer products. For small companies that manufacture or import PFAS, EPA’s announced reporting proposal augurs a more aggressive stance and increases compliance procedures and costs for entities that may have previously had limited exposure to TSCA regulation. For larger, publicly-traded names, beyond non-material costs that may arise (as in the case of EPA’s approval of the Chemours testing petition), increased reporting and testing requirements will significantly increase litigation costs as reporting requirements enhance public understanding of PFAS contamination. This risk is especially heightened if increased testing results in more robust science around existing linked human health conditions—like kidney and testicular cancers, ulcerative colitis, and thyroid disease. Or potentially unveil new ones.

The Growing Munitions Supply Chains Bottleneck

Capstone believes that munitions supply chains, particularly for critical component parts, represent a significant opportunity for private equity investors. Diversifying and rapidly scaling the industrial base for munitions is a top priority of the Department of...