By: Grace Totman

May 23, 2022 — Earlier this year, I spent a handful of afternoons at a BioLife Plasma Services center just outside of Washington, DC. What started as background research for a Capstone due diligence project turned into a behind-the-scenes insight into a little-known $24 billion industry: plasma donation. My first donation took three hours from start to finish and included a thorough physical, screening, and medical history. Follow-up donations took just an hour or so. Each donation was relatively painless and frankly enjoyable: donors chatted about weekend plans while a movie played quietly in the corner of the room. And each visit ended the same way, with a technician handing me a prepaid debit card ranging from $100-$145. These would later pay for a couple of trips to Trader Joe’s. I haven’t returned to the BioLife center since February, and yet, every couple of days, emails with enticing subject lines flood my inbox: $600 for a month of donations increases to $700, and then even further the longer I go without returning.

I haven’t returned to the BioLife center since February, and yet, every couple of days, emails with enticing subject lines flood my inbox: $600 for a month of donations increases to $700, and then even further the longer I go without returning.

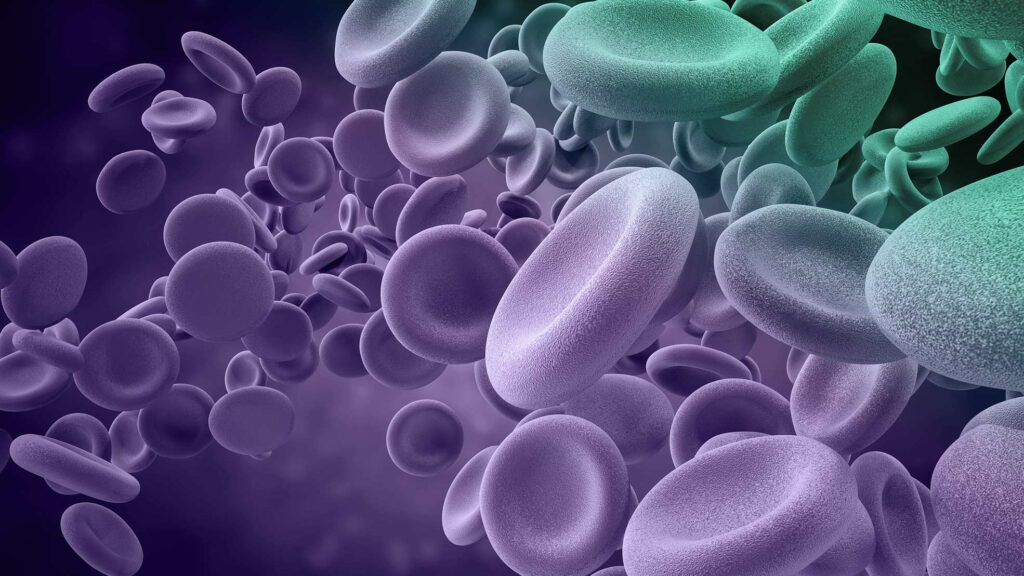

Ask most people and they’ll say they’ve donated blood (around 50% of Americans have at least once) but ask about plasma, and far fewer individuals even know of its existence, despite the lucrative donation process. Plasma, the liquid component of blood, contains vital proteins and electrolytes used to manufacture life-saving treatments for cancer and immune disorders, among other diseases. More than 125,000 Americans rely on plasma-derived medications, and as researchers continue to discover new uses for this liquid gold, the number will only grow. The plasma market has produced a highly consolidated for-profit space dominated by CSL Behring, Grifols, and Takeda, which collect more than 90% of source plasma. Parallels can be drawn with the dialysis industry: both are highly consolidated and operate out of unremarkable retail locations.

Demand for plasma is high and growing by 6%-10% annually. An individual with hemophilia needs 1200 donations of plasma for just one year of treatment. Growing demand, compounded by a significant reduction in donations during the pandemic, is now outstripping supply, prompting the US Food and Drug Administration to announce a shortage of some plasma products and forcing many patients to lengthen the time between treatments or reduce doses.

The answer to the shortage seems simple: pay more money for donations to get more donors. Paid plasma donation, however, is highly controversial. The US is the only country that allows for truly unregulated paid donations. While a handful of European Union countries allow for limited payment, the world largely relies on US donations, which provide over 70% of plasma globally. Opposition to paid donations of any kind (blood, plasma, organs) stems from three main arguments: 1) Paid donations are more likely to be diseased given the donor pool attracted; 2) Paid donations take advantage of disadvantaged populations; and 3) Paid donations discourage unpaid donations.

In response to such concerns, the World Health Organization (WHO) passed a resolution in 1975 urging member states to use voluntary unpaid donations of blood and blood components (plasma). The WHO has since repeatedly reaffirmed its commitment to voluntary unpaid plasma donations, most recently in 2014, when it announced a goal of sourcing 100% of the world’s plasma from unpaid donations by 2020 (a goal that was far from met).

However, the arguments against paid donation have now largely been disproven. Washing and freezing technologies developed in the 1990s have essentially eliminated the risk of transmitting contaminated plasma. Even before this point in the process, extensive screening and testing weeds out many donors. While donors tend to be low-income, adverse reactions occur in less than 0.03% of cases, and donation centers have come to be seen as valued safety-net providers. Visits include valuable blood testing and physical screenings, and centers are mandatory reporters of HIV and Hepatitis C.

Most donors recognize that while the ethical considerations of donating “feel good,” the money is the real draw.

Finally, researchers have found that paid plasma donation actually increases unpaid donation. As a bonus, paid donations not only provide income, but can also provide a sense of purpose and community. During my donations, many of the other donors greeted each other warmly: they’ve been coming at the same time for years. Most donors recognize that while the ethical considerations of donating “feel good,” the money is the real draw. One man at a neighboring machine was using his donation to buy his son a toy truck, while several college students nearby were chatting about the upcoming weekend—their donations were going towards a beer fund.

The plasma shortage has driven payment amounts to record highs. Based on the pre-pandemic average payment of $50 per donation, donors could make $5,200 a year given the maximum limit of 104 donations annually. Today, with the average donation hovering closer to $150, donors can make up to $15,600 annually, or 115% of the federal poverty line. And yet, donations remain rare, plasma centers struggle to attract new donors, and most Americans remain unaware of the financial upside. As such, per-donation payments are likely to continue to rise. And with opposition to paid donation elsewhere remaining entrenched, the prospects for the US plasma industry remain bright. Rising demand may eventually force other countries to revisit their plasma donation policies and allow paid donation, but for now, American plasma truly is liquid gold. Capstone remains constructive on the overall plasma market, particularly as pandemic-related shortages dissipate. Demand is likely to continue to rise, and supply is essentially uncapped—a renewable resource running through our veins, and a lucrative one at that.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Grace Totman

Vice President, Healthcare

Read More from Grace

From Death Panels to Duopoly: How Dialysis Coverage has Changed & Looming Risks for Providers

Healthcare Insurance 2022 Policy Outlook

The Smartest Insurers in the Room: How Medicare Advantage Insurers Continue to Evade